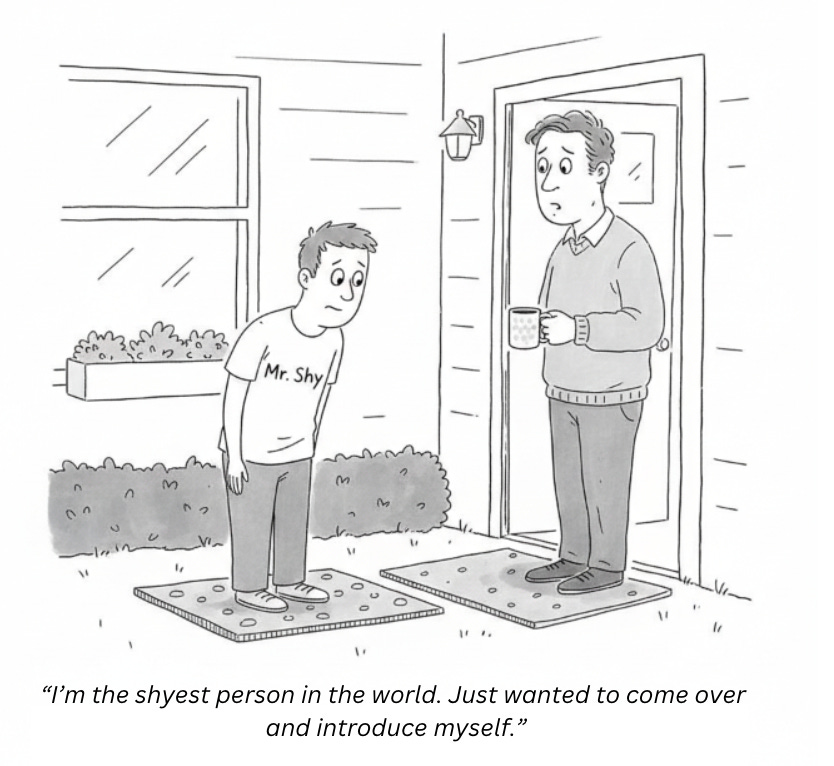

Solutions are shy

Keep looking for clues. Mr Shy is out there.

You’re dropped into a new city and have one job: Find Mr Shy.

Here’s the catch: Mr Shy will never introduce himself to you. He’s awfully shy.

Mr Shy isn’t on a poster, Mr Shy won’t call your phone, and Mr Shy won’t knock on your door and say: “Hi, I’m Mr Shy”.

Mr Shy is sometimes hiding in plain sight across the room, but you don’t want to believe it’s him, other times he’s hiding in the dangerous part of town underneath a closed-down Italian restaurant called San Carlo’s.

How would you find Mr Shy?

Finding Mr Shy is what it’s like solving a problem.

The more difficult the problem is, the shyer the solution will be — or the shyer Mr Shy will be: There’s more locations Mr Shy could be in, people are trying to stop you from meeting Mr Shy, people are judging you for wanting to find Mr Shy, there are thousands of people that look like Mr Shy, rooms you think Mr Shy might be in bring up memories of where you failed looking for Mr Shy in the past or people say it’s impossible to find Mr Shy.

I’m going to give 4 different stories of people finding Mr Shy, and what lessons we can take for finding our own Mr Shy.

The first story is about why it’s important to believe Mr Shy is always out there. Let’s begin.

1.

In 1939, mathematician George Dantzig wrote to legendary professor Jerzy Neyman to study under him at Berkeley. Neyman accepted. Dantzig tells what happened next:

“During my first year at Berkeley I arrived late one day to one of Neyman’s classes. On the blackboard were two problems which I assumed had been assigned for homework. I copied them down. A few days later I apologised to Neyman for taking so long to do the homework—the problems seemed to be a little harder to do than usual. I asked him if he still wanted the work. He told me to throw it on his desk. I did so reluctantly because his desk was covered with such a heap of papers that I feared my homework would be lost there forever.

About six weeks later, one Sunday morning about 8 o’clock, Anne and I were awakened by someone banging on our front door. It was Neyman. He rushed in with papers in hand, all excited: “I’ve just written an introduction to one of your papers. Read it so I can send it out right away for publication.” For a minute I had no idea what he was talking about. To make a long story short, the problems on the blackboard which I had solved thinking they were homework were in fact two famous unsolved problems in statistics. That was the first inkling I had that there was anything special about them.”

The number one reason people don’t find Mr Shy is that they believe he doesn’t exist.

That’s his speciality: If people think he doesn’t exist, they won’t even bother looking for him. The next time you hear your mind describe something as: “Unsolvable”, “Can’t be done” or “Unrealistic” — that’s Mr Shy’s propaganda campaign.

If you go into a problem thinking Mr Shy exists, there’s no guarantee you’ll find Mr Shy. But if you go into a problem thinking Mr Shy doesn’t exist, there’s a guarantee you’ll never find him because you won’t look.

That’s why it’s important to remind yourself: Solutions are shy.

George Dantzig was an incredible mathematician who would go on to win the National Medal of Science, but his advantage that day was being naive; he carried on because he believed his task was homework.

The easiest way to get into Dantzig’s state of mind is when faced with a problem, ask yourself the golden question: Does solving this problem defy the laws of physics? Your brain will answer no and start to view it as a solvable problem.

Now, let’s go and meet a very angry man trying to walk his unwalkable dog.

2.

Scott Adams, the creator of the cartoon Dilbert, spent years in frustration walking his dog:

“For years I found it annoying to walk my dog. All she ever wanted to do was sniff the grass and trees upon which other dogs had left their scent. Neither of us got much exercise. It was like tug-of-war to get Snickers to move at all.”

Adams felt like a failure for years and could not find a solution to make his dog want to go on a walk. One day, he was watching a video of a dog expert explain that “dogs might need the sniffing more than the walking. Their brains light up when they sniff, and it can tire them out when they engage in vigorous sniffing.”

Though the video wasn’t explicitly about Adam’s problem, that’s when he immediately considered its implications, Adams could hear whispers of Mr Shy:

“I had noticed how happy Snickers looked when sniffing, but my brain couldn’t connect the dots because sniffing dog urine sounds inherently unpleasant to my human brain. But to the dog, it was the equivalent of checking her social media. I started naming the trees and shrubs in the park accordingly: Muta (formerly known as Facebark), Twigger, LeafedIn, Instabush, and Treemail. Obviously, the garbage receptacle into which people flung their dog poop bags was TikTok. Once I understood the importance of sniffing, I reframed my experience this way.

Usual Frame: Taking the dog for a walk and failing.

Reframe: Taking the dog for a sniff and succeeding.

That reframe completely changed my subjective experience. Instead of failing at walking, I was succeeding at being a sniff-assistant.”

The second biggest error when it comes to finding Mr Shy is starting with a false assumption about him that you don’t even think to question.

You frantically look all over town for a man who has a mullet, when he’s actually bald. Or in Adams case, the dog is broken, and I’m a bad owner.

In Adams’ case, Mr Shy was there the entire time in front of him on that walk each day — he just never once thought to question: Why is the dog sniffing?

His entire model of what Mr Shy looked like was stacked on top of the wrong foundation: Why doesn’t this dog want to walk?

Useful rules of thumb when it comes to assumptions:

1. Assume the problem is a side problem. The main problem is usually how you’re viewing the problem. If you solve the main problem, the solution for the side problem often reveals itself. You often find yourself outside of Mr Shy’s house.

2. Assume your first 5 thoughts about Mr Shy are wrong. He loves to spread false propaganda about himself.

Now, let’s go and meet a young James Cameron trying to find Mr Shy in Jamaica.

3.

It’s 1981.

James Cameron, who would go on to direct 3 of the 4 highest-grossing movies of all time: Titanic and the Avatar franchise, has arrived in Jamaica.

Cameron is set to shoot his first-ever film: Piranha II.

Unlike Titanic and Avatar, which had a budget of $200 million and $237 million, respectively, Piranha II has a budget of $145,000.

As he steps off the plane, he drives over to meet the production team to see the rundown of the locations they’d secured for filming.

Cameron finds out there is no rundown because they’ve not secured one location for the film.

Cameron thought his team had found Mr Shy for him, and now Mr Shy was long gone.

Before looking at what Cameron did next, ask yourself: If you arrived in a foreign country to shoot your first ever film and found out days before it was to start that there were no locations secured, how would you react? How would you find Mr Shy?

Here’s the list of low agency responses my brain came up with: Conclude I’m not cut out for the movie business, get angry at my production team and call them amateurs, go back home, go to the beach, delay the shoot, fantasise about an alternative reality where they secured the location and I get angrier and angrier looping on why I’m not in that version of reality.

Here’s what Cameron did next, as described in The Futurist, Rebecca Keegan’s biography of James Cameron:

“He ripped open the petty cash drawer, grabbed all the money and a Polaroid camera and stormed out. On the sidewalk, Cameron flagged down the first person he saw, a young Jamaican guy with a battered white car, and offered him some cash to drive him around for a day.”

By the end of the day, Cameron had visited a hotel, a school, a police station, asked to speak to the person in charge, negotiated a deal in cash to film there, created handwritten contracts on pieces of paper on the spot and secured filming locations.

Just because someone else lost Mr Shy doesn’t mean he can’t still be found — but watch out, he loves to hide behind your anger and rumination of what could’ve been.

What James Cameron did to find Mr Shy wasn’t rocket science. He just asked: What’s the simplest route from where I am now and where I want to get to?

One of the best tweets I’ve ever read on this comes from Indigo: “When you miss a turn, your GPS doesn’t judge you, it recalculates. No matter how many detours you take, it finds another way forward. Life works like that too. You’ll make mistakes, but your destination doesn’t vanish. The route just changes.”

Forget all past attachments to Mr Shy. What’s the simplest route to find him today?

Now, one more final story about a phone call.

4.

In 1967, Bill Hewlett, the co-founder of Hewlett-Packard, one of the largest technology companies in the 1960s, was relaxing at his home in San Francisco.

His landline starts to ring, so he picks up the phone:

“Hello, Bill Hewlett speaking”

“Hi, I’m a twelve-year-old boy. I want to build a frequency counter for a science project, and was wondering if you have any spare parts that I could borrow?”

Bill Hewlett asks how he got his number.

“I found it in the yellow pages”

Bill bursts out laughing, agrees to give the 12-year-old the spare parts and offers him an internship at HP for his boldness.

That 12-year-old boy, Steve Jobs, would later recall how this moment shifted his perspective on life:

“Most people never pick up the phone and call. Most people never ask. And that’s what sometimes separates the people who do things from the people who just dream about them. You gotta act. And you gotta be willing to fail, you gotta be ready to crash and burn. I’ve never found anyone who said no or hung up the phone when I called. I just asked. And when people ask me, I try to be as responsive, to pay that debt of gratitude back.”

One of the simplest ways to find Mr Shy is to ask other people if they’ve seen him, or if they can show you where he is.

54-year-old Bill Hewlett, with 12,000 employees, isn’t going to pick up the phone and call a 12 year old about his science project to help him.

The people who know Mr Shy aren’t going to pick up the phone and tell you about him: You must ask.

When asking for other people to help you find Mr Shy, be polite, be specific, and keep going. If someone won’t help, that’s the work of Mr Shy trying to hide; keep going.

If you’re polite and specific, not only will lots of people help you find Mr Shy, they’ll root for you and want to be part of the mission. Everyone can relate to when they were looking for Mr Shy.

So, next time you find yourself hunting Mr Shy, remember:

1. Mr Shy exists - Unless your problem defies the laws of physics, it’s a solvable problem.

2. Mr Shy is deceptive - Question all assumptions. Don’t trust your first thoughts about a problem.

3. Mr Shy could be right in front of you - What is the simplest step from A to B? If I turned on GPS brain and looked at this problem fresh, how would I approach it?

4. Ask if anyone has seen Mr Shy - Who do I know that might have an idea about this problem? Can I send them a polite and specific question?

PS. Speaking of step 4, can you help me find Mr Shy? If you have any Mr Shy stories, include them in the comments section.

I was a wrestler at a small college in rural Kentucky. The school was small, the town was small, and our schedule between school and practice was packed. But my best friend and I, we desperately wanted a part time job. Just to have a little cash. We couldn't afford to go bowling, get drunk, or go to the movies. Neither of us had a cent to our name. Someone told us a car mirror factory was hiring for night shift-the only time we were available. We applied. They rejected us. A week later, that someone told us its a shame we didn't get hired. They did, and they were headed to an introductory onboarding for new employees happening. We went. They asked who we were. We said, "we're uh, the college kids the factory uh, hired to ya know, kinda help out at night." They were puzzled, but miraculously, someone overheard and said, "I think I heard about them comin' on board." Who knows what they heard, but couldn't have been that. Either way, we were onboarded that day, and spent the next three years working four hours a night building Lexus mirrors. We were the richest kids on the team, making 10 bucks an hour.